Psychosomatic Philokalia

Exploring the convergence of ancient Orthodox spiritual disciplines and modern psychological therapies for holistic well-being.

Orthodox spirituality and psychology

Understand, alleviate psychosomatic conditions

Holistic person (spirit, soul, body)

Logismoi, Passions, Nepsis

CBT, mindfulness, somatic therapy

Ancient Orthodox Christianity

Prayer, Fasting, Confession

| Orthodox Concept | Description | Psychosomatic/Therapeutic Parallel | Key Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logismoi | Troublesome thoughts, suggestions, mental images. | Intrusive thoughts, automatic negative thoughts, cognitive distortions. | Evagrius Ponticus, Desert Apophthegmata |

| Passions | Disordered desires, habitual emotional states (e.g., anger, sadness, fear). | Emotional dysregulation, maladaptive coping mechanisms, entrenched behavioral patterns. | John Cassian, The Philokalia |

| Nepsis (Watchfulness) | Vigilance of the mind, guarding the heart. | Mindfulness, metacognitive awareness, attentional control. | Hesychastic Fathers, Theoria of Light |

| Metanoia (Repentance) | Change of mind/heart, reorientation towards God, acknowledging wrong. | Cognitive restructuring, behavioral change, acceptance and commitment, trauma processing. | Scriptural teachings (e.g., Jesus' call to repent), Patristic writings |

| Jesus Prayer | Repetitive invocation, focused attention, bringing mind to heart. | Mindfulness meditation, mantra meditation, somatic grounding techniques. | Hesychastic tradition, Saint Sophrony Sakharov (writings) |

| Hesychia (Stillness) | Inner quietude, silence of the mind and passions. | State of calm, nervous system regulation, non-reactive awareness. | Gregory Palamas, Philokalia texts on stillness |

| Philanthropia | Love for humanity, compassion, active kindness. | Empathy, prosocial behavior, therapeutic alliance, compassion-focused therapy. | Lives of Saints, Patristic homilies |

| Phronema (Mindset) | Way of thinking, orientation of the Nous, spiritual disposition. | Cognitive schemas, mindset, internalized beliefs, core self-concept. | Patristic writings on the renewal of the mind |

| Gerontia/Spiritual Guide | Experienced mentor offering counsel and support. | Therapeutic relationship, mentorship, guidance in recovery. | Monastic traditions, lives of spiritual fathers/mothers |

The exploration of the inner life and its connection to physical and mental well-being has been a central concern across various traditions and disciplines throughout history. Within the framework presented by Psychosomatic Philokalia, the focus is placed on the dialogue and unexpected convergences between the ancient spiritual teachings of early Orthodox Christianity—from the pronouncements of Jesus and the writings of the Church Fathers to the practices of Desert monastics, later mystics, and contemporary theological reflections—and modern psychological approaches aimed at understanding and alleviating psychosomatic conditions. This field examines how centuries-old spiritual disciplines, rooted in a holistic anthropology that views the human person as an integrated unity of spirit, soul, and body, offer insights and practices that resonate with, or even anticipate, methods employed in contemporary therapeutic modalities such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based interventions, somatic experiencing, and trauma-informed care.

Psychosomatic Philokalia posits that the struggles described by early Christian ascetics against inner disquiet, disordered thoughts, and emotional turmoil bear striking resemblances to modern clinical descriptions of conditions like anxiety, depression, and stress-related physical ailments. The Christian understanding of the nous (often translated as mind or intellect, but encompassing the heart's perceptive faculty), the concept of logismoi (troubling thoughts or suggestions), and the development of passions (disordered desires or emotional states) provides a framework for understanding inner conflict that finds intriguing parallels in psychological models of cognitive distortions, intrusive thoughts, and emotional dysregulation. The path to spiritual health, as articulated in the Orthodox tradition, involves disciplines like watchfulness (nepsis), repentance (metanoia), prayer (especially the Jesus Prayer), fasting, and Confession. These practices, when examined through a psychological lens, reveal sophisticated techniques for self-awareness, emotional processing, behavioral modification, and the cultivation of inner peace, which align in significant ways with therapeutic goals and techniques used today to address psychosomatic suffering. The historical development of these spiritual methods, particularly within the monastic traditions of the Egyptian desert and later centers like Mount Athos, offers a rich source of experiential knowledge regarding the human psyche and its capacity for transformation, providing a unique perspective on healing that integrates spiritual, psychological, and physical dimensions.

Historical Roots and Foundational Concepts

The origins of the Orthodox approach to human suffering and healing are deeply embedded in the ministry and teachings of Jesus Christ himself, whose acts of healing were often understood not merely as physical cures but as integral to a restoration of the whole person—body, soul, and spirit. This holistic view was further elaborated by the Apostles and early Church Fathers, who began to articulate a theological anthropology that emphasized the interconnectedness of the human faculties and the impact of sin and disordered states on both inner and outer well-being. Key figures like the Apostle Paul, in his epistles, frequently discussed the struggle between the "flesh" and the "spirit" (e.g., Romans 7), a theme that would later be interpreted by patristic writers as the conflict between fallen human nature and the potential for renewal and divine likeness. This early period laid the groundwork for understanding inner turmoil not just as moral failing but as a state of spiritual and psychological illness requiring specific forms of spiritual discipline and divine grace for healing.

Desert Fathers confronting troublesome thoughts (logismoi) and disordered passions through asceticism and self-observation.

Desert Fathers confronting troublesome thoughts (logismoi) and disordered passions through asceticism and self-observation.Following the era of persecution, the rise of monasticism in the 3rd and 4th centuries, particularly in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, became a crucible for the systematic development of practices aimed at confronting the inner landscape. The Desert Fathers and Mothers, through intense Asceticism and constant vigilance, gained profound insights into the workings of the mind and the nature of temptation and disordered thoughts. Their Apophthegmata (Sayings) and the writings of figures like Evagrius Ponticus and John Cassian provide detailed taxonomies of logismoi and passions, offering practical guidance on how to identify, resist, and transform them. This monastic wisdom, codified and passed down through generations, represents an early form of empirical psychology, based on rigorous self-observation and guided by experienced spiritual mentors (Geronda or Starets). This historical trajectory demonstrates a continuous concern within the tradition for the state of the inner person and its profound impact on overall health, anticipating modern psychosomatic perspectives that recognize the mind's influence on the body and vice versa.

Patristic Synthesis of Soul and Body

The Church Fathers, building upon scriptural foundations and early monastic experience, developed a sophisticated understanding of the human person as a hypostasis (a unique, integrated individual) created in the image and likeness of God. Figures like Gregory of Nyssa and Maximus the Confessor explored the intricate relationship between the soul (comprising intellect, will, and emotion) and the body, rejecting dualistic notions that separate the two. They understood that the fall from grace introduced corruption and disorder not just into the spiritual and mental faculties but also into the physical body, leading to suffering and mortality. Consequently, the path to salvation and healing (Theosis, or deification) was seen as a process involving the sanctification and restoration of the entire human being.

This patristic synthesis provides a theological and philosophical basis for understanding psychosomatic illness. Disordered thoughts (logismoi) and unchecked passions were understood to weaken the soul, which in turn could manifest as physical ailments. Conversely, physical deprivations or illnesses could also impact the state of the soul and mind. The Fathers emphasized the importance of restoring the nous to its proper function—a state of clarity, watchfulness, and union with God—as essential for the health of the whole person. This perspective highlights the interconnectedness of spiritual, psychological, and physical health, a view that resonates strongly with contemporary holistic health models and the specific focus of psychosomatic medicine. The writings of these early theologians offer a framework for understanding the complex interplay between inner states and physical manifestations that predates modern scientific inquiry into the mind-body connection.

The Desert Ascetics and Inner Taxonomy

The monastic movement in the desert, particularly in Egypt from the 3rd century onwards, became a practical laboratory for understanding and combating the inner forces that lead to suffering. Figures like Abba Anthony the Great, Abba Poemen, and Amma Syncletica, through their relentless struggle against temptation and self-deception, developed a detailed phenomenology of the inner life. Evagrius Ponticus, a prominent intellectual figure among the Desert Fathers, provided a systematic categorization of the eight principal logismoi or evil thoughts: gluttony, lust, avarice, sadness, anger, acedia (spiritual sloth), vainglory, and pride. He meticulously described how these thoughts arise, how they interact, and how they can lead to the development of corresponding passions.

Evagrius and others taught that these logismoi are not merely abstract concepts but powerful suggestions or images that enter the mind, seeking assent. If entertained and acted upon, they gain strength and become entrenched as passions, which are described as habitual, disordered movements of the soul that enslave the will and obscure the nous. This detailed taxonomy and understanding of the progression from fleeting thought to ingrained passion offers a striking parallel to modern cognitive models that describe how automatic negative thoughts can lead to distorted beliefs and habitual emotional/behavioral responses, contributing to psychological distress and psychosomatic symptoms. The Desert Fathers' emphasis on identifying the initial thought (logismos) and cutting it off before it takes root is a practice remarkably similar to techniques used in cognitive restructuring in CBT, where clients learn to identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns.

Spiritual Disciplines and Therapeutic Parallels

The Orthodox tradition offers a rich array of spiritual disciplines aimed at purifying the heart and transforming the inner person. These practices, developed over centuries, were designed to cultivate self-awareness, strengthen the will, reorient desires, and open the individual to divine grace. When examined through a psychological lens, these disciplines reveal sophisticated methods for self-regulation, emotional processing, and behavioral change that bear significant parallels to techniques employed in modern therapy. The goal in both contexts is often to move from a state of reactivity and suffering to one of greater freedom, peace, and integrated functioning.

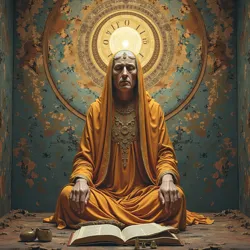

Practitioner focused on the heart, using repetitive prayer to cultivate inner stillness (hesychia) and attention (nepsis).

Practitioner focused on the heart, using repetitive prayer to cultivate inner stillness (hesychia) and attention (nepsis).Disciplines such as prayer, fasting, and asceticism are not merely external rituals but are understood as tools for inner work. Prayer, particularly the Jesus Prayer ("Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me"), is a practice of focused attention and invocation that aims to bring the mind into the heart and cultivate a state of continuous communion with God. Fasting and asceticism involve voluntary self-denial and physical discipline, intended to weaken the hold of the passions associated with the body and senses, making the individual more receptive to spiritual realities. Confession, the honest disclosure of one's thoughts and actions to a spiritual father or priest, provides a space for accountability, receiving guidance, and experiencing forgiveness and reconciliation. These practices, while rooted in a theological framework, have demonstrable effects on psychological states and behavior.

The Praxis of Prayer and Focused Attention

Prayer, in its various forms, is central to Orthodox life, but the Jesus Prayer holds particular significance for its use as a tool for cultivating inner stillness and focused attention. The repetitive invocation of the name of Jesus, often combined with regulated breathing and a focus on the heart center, is a practice with clear parallels to modern mindfulness and meditation techniques. Both aim to train the mind to remain present, to observe thoughts without identification, and to cultivate a state of calm awareness.

The practice of the Jesus Prayer is explicitly linked to the concept of nepsis or watchfulness, the vigilant guarding of the mind against distracting or harmful thoughts (logismoi). By repeatedly returning the attention to the prayer, the practitioner learns to recognize the arising of thoughts and gently redirect the mind. This process strengthens the capacity for attentional control and metacognition (awareness of one's own thought processes), key components targeted in mindfulness-based therapies and CBT. The goal is not to suppress thoughts but to detach from them, preventing them from developing into passions. The rhythmic nature of the prayer and its focus on the breath and body also connect it to somatic practices that emphasize grounding and body awareness as pathways to regulating the nervous system and processing emotional distress.

Fasting, Asceticism, and Somatic Regulation

Fasting and other forms of ascetic discipline, such as voluntary poverty, solitude, or prolonged standing during prayer, are integral to Orthodox spiritual life. These practices involve the conscious regulation of bodily needs and desires. While rooted in theological motives related to self-denial and solidarity with Christ's suffering, they also have significant psychological and somatic effects. By voluntarily restricting food intake or engaging in physical exertion, ascetics learn to tolerate discomfort, distinguish between genuine needs and disordered cravings, and gain mastery over impulsive behaviors.

From a psychosomatic perspective, fasting and asceticism can be seen as forms of behavioral activation and exposure therapy. They challenge habitual patterns of seeking comfort and avoiding discomfort, building resilience and tolerance for difficult physical and emotional states. The discipline involved in adhering to fasting rules requires significant self-control and planning, strengthening executive functions. Furthermore, the physical sensations experienced during fasting or asceticism can bring the practitioner into greater awareness of their bodily state, a form of interoceptive awareness that is increasingly recognized as important for emotional regulation and trauma recovery in somatic therapies. The intentional engagement with physical discipline serves to integrate the body into the spiritual path, recognizing its role in the overall health and transformation of the person. The historical development of specific fasting periods and monastic rules, such as those found in the Typikon (rule book) of monasteries like the Studion or Mount Athos, reflects a sophisticated, time-tested understanding of how physical practices impact the spiritual and psychological state.

Confession, Accountability, and Narrative Integration

The sacrament of confession, or spiritual direction (gerontia), provides a crucial space for the honest disclosure of one's inner struggles, thoughts, and actions. This practice involves articulating one's difficulties to a trusted spiritual guide (a priest or experienced monastic) who offers counsel, prayer, and absolution. This process of vocalizing inner turmoil, taking responsibility for one's choices, and receiving guidance and spiritual support has powerful therapeutic effects that align with aspects of psychodynamic therapy, narrative therapy, and trauma-informed care.

In confession, the individual is encouraged to examine their conscience (logismoi, passions, deeds) in detail. This act of verbalizing one's inner world brings unconscious or semi-conscious thoughts and feelings into conscious awareness. Sharing these struggles with another person breaks down isolation and shame, which often fuel psychological distress and psychosomatic symptoms. The spiritual guide's role is analogous in some ways to that of a therapist: providing a non-judgmental presence, helping the individual gain perspective on their difficulties, identifying recurring patterns, and offering strategies for change. The act of receiving forgiveness (in sacramental confession) can facilitate the release of guilt and self-condemnation, freeing up energy for healing. Furthermore, the process of recounting one's struggles helps to create a coherent narrative, integrating fragmented experiences and fostering a sense of agency and hope for the future. This practice, deeply embedded in the communal life of the Church, highlights the importance of relationship and accountability in the journey towards healing and wholeness.

The Nature of Inner Struggle: Passions and Thoughts

The Orthodox understanding of the inner struggle is profoundly psychological in its description, even while rooted in a theological context of the effects of the fall and the influence of malevolent spiritual forces. The primary locus of this struggle is the nous (mind or heart), where logismoi (thoughts, suggestions) arise. These logismoi are not seen as inherently one's own initially but as external suggestions that seek entry and assent. The battle is to discern their origin and nature and to reject those that lead away from God and towards self-destruction. Failure to do so allows the logismos to implant itself and eventually develop into a passion.

Passions (πάθη, pathē) are understood as deep-seated, often habitual, disordered states of the soul that manifest as compulsive desires, negative emotions, and distorted ways of perceiving reality. The traditional list includes the eight mentioned by Evagrius (gluttony, lust, avarice, sadness, anger, acedia, vainglory, pride), although later Fathers sometimes consolidated or reordered them (e.g., focusing on the root passions of pride and self-love). These passions are not merely feelings but are seen as energies of the soul that have been corrupted and misdirected, leading to suffering for oneself and others. They are viewed as the root cause of much psychological and psychosomatic distress, clouding the nous and preventing genuine connection with God and fellow human beings. Overcoming the passions is therefore central to the path of spiritual and psychological healing.

Logismoi and Cognitive Distortions

The concept of logismoi bears a striking resemblance to automatic negative thoughts and cognitive distortions as described in cognitive behavioral therapy. Logismoi are often described as fleeting, unbidden thoughts or images that pop into the mind. They can be tempting, accusatory, despairing, or distracting. The Desert Fathers became experts at observing these thoughts, identifying their source (seen as external temptation or arising from existing passions), and understanding their deceptive nature. For example, a logismos of sadness might arise after a minor setback, suggesting hopelessness and worthlessness, much like a cognitive distortion of catastrophizing or personalization.

The practice of nepsis (watchfulness) is the primary method for dealing with logismoi. It involves cultivating a state of alert, sober awareness of one's inner landscape. The practitioner learns to "stand at the door of the mind," observing the thoughts that seek entry without immediately identifying with them or acting upon them. This mirrors the process in CBT of learning to identify automatic thoughts and examine their validity and helpfulness, rather than accepting them as truth. The goal is to challenge the logismos before it gains power. Early Christian texts describe this as "cutting off the logismos," a decisive act of rejection based on discernment, preventing the thought from triggering an emotional cascade or behavioral response that reinforces the underlying passion. This active engagement with thought patterns is a key point of convergence between ancient spiritual discipline and modern cognitive restructuring techniques.

Passions and Emotional Dysregulation

The passions are understood as the deeper, more entrenched consequences of repeatedly assenting to logismoi. They are described as powerful, habitual inclinations that distort perception, motivate harmful behaviors, and cause significant inner suffering. For instance, the passion of anger is not just a fleeting feeling but a pervasive state of irritability, resentment, and hostility that colors one's interactions and internal experience. The passion of acedia is a profound spiritual and psychological lassitude, a combination of boredom, despair, and aversion to spiritual effort, which shares characteristics with clinical depression and anxiety.

Overcoming the passions is a lifelong process in the Orthodox tradition, requiring sustained effort, divine grace, and the practice of virtues that are the positive counterparts to the passions. For example, the passion of anger is countered by meekness and patience; gluttony by temperance; sadness by spiritual joy and hope. This process of cultivating virtue to overcome disordered states aligns with therapeutic approaches that focus on building positive coping skills and emotional regulation strategies to counteract maladaptive patterns. Somatic therapies, which address the bodily manifestations of trauma and chronic stress, also resonate with the Orthodox understanding that passions are deeply embodied and require work on the physical level (through fasting, prostrations, etc.) as well as the mental and spiritual. The integrated nature of the passions, affecting mind, body, and soul, underscores the psychosomatic dimension of the inner struggle as understood in this tradition.

Paths to Healing and Transformation

The Orthodox path is fundamentally one of healing and transformation, moving from the state of being dominated by passions and logismoi towards theosis, the likeness of God. This journey involves not just the suppression of negative states but the active cultivation of virtues and the restoration of the nous to its natural, healthy state—illumined by divine grace and capable of true discernment and love. The means to this healing are multi-faceted, involving personal ascetic effort, the grace of the Sacraments, guidance from spiritual elders, and the supportive context of the Church community.

Key concepts in this process include metanoia (repentance), nepsis (watchfulness), and the cultivation of phronema (the Orthodox mindset or way of thinking). Metanoia is more than just feeling sorry for one's sins; it is a fundamental change of mind and heart, a reorientation of one's entire being towards God and away from self-destructive patterns. Nepsis, as discussed earlier, is the vigilant guarding of the inner world, essential for discerning and rejecting harmful thoughts. Phronema represents the internalization of the teachings and spirit of the Church, leading to a transformed way of perceiving and responding to life. These concepts describe a process of deep psychological and spiritual restructuring that aims at lasting change.

Metanoia as Cognitive and Behavioral Change

Metanoia, often translated as repentance, literally means "change of mind." In the Orthodox context, it signifies a profound reorientation of one's will, thoughts, and desires towards God. This involves acknowledging one's fallen state and the presence of passions and logismoi, taking responsibility for one's actions, and actively turning towards a different way of living. This concept aligns remarkably well with the core principles of cognitive and behavioral change in modern therapy.

Therapeutic approaches like CBT and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) emphasize the importance of identifying maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors, understanding their consequences, and committing to making conscious changes. Metanoia encompasses this process of self-awareness and volitional change. It involves recognizing the futility and destructiveness of living according to the passions and making a conscious decision to pursue a virtuous life. This is not seen as a one-time event but a continuous process of self-examination, confession, and renewed effort. The emphasis on the "change of mind" aspect of metanoia highlights the cognitive component—transforming one's way of thinking and perceiving—while the call to "bear fruits worthy of repentance" emphasizes the behavioral component—demonstrating the inner change through outward actions. This integrated approach to inner and outer transformation is central to both Orthodox spiritual healing and effective psychological therapy.

Nepsis and Cultivating Self-Awareness

Nepsis, or watchfulness, is the state of vigilant attentiveness to the inner movements of the soul—the thoughts, feelings, and intentions that arise. It is the practice of sober awareness, guarding the nous against distraction and deception. This concept is perhaps the most direct parallel between Orthodox spiritual practice and modern mindfulness techniques. Both involve training the attention to observe inner phenomena without judgment or immediate reaction.

In mindfulness, the practitioner learns to notice thoughts and feelings as transient events in the mind, rather than identifying with them as defining truths. Similarly, nepsis teaches the practitioner to recognize logismoi as external suggestions or products of the passions, which can be rejected rather than acted upon. This ability to create space between stimulus (thought/feeling) and response is crucial for developing emotional regulation and breaking free from compulsive behaviors driven by passions. The cultivation of nepsis is considered essential for spiritual progress and inner peace, as it allows the nous to remain clear and discerning, less susceptible to the turbulent influence of unexamined thoughts and emotions. This practice of sustained self-awareness is a foundational skill for addressing a wide range of psychological difficulties, including those that manifest psychosomatically.

Philanthropia and Compassion-Focused Healing

The concept of philanthropia—God's love for humanity and the call for humans to love one another—is fundamental to Orthodox theology and ethics. Compassion, both for oneself and others, is not merely a feeling but an active orientation of the heart and a practice essential for healing. The virtues cultivated in overcoming the passions, such as meekness, patience, humility, and love, are all expressions of philanthropia. This focus on relationality and compassionate engagement has significant implications for psychological well-being and healing.

In contemporary therapy, particularly compassion-focused therapy (CFT) and trauma-informed care, the cultivation of self-compassion and compassion for others is recognized as crucial for overcoming shame, building resilience, and fostering secure attachment patterns. The Orthodox tradition, through its emphasis on philanthropia, the lives of the saints as examples of radical love and forgiveness, and the communal nature of the Church, provides a powerful framework for understanding the healing power of compassion. Confession, for instance, is an act of receiving God's philanthropia through the ministry of the Church, which enables the individual to extend compassion to themselves and others. The monastic emphasis on hospitality and service also reflects the practical application of philanthropia as a means of overcoming self-absorption and cultivating connection. This relational and compassionate dimension highlights how healing is not solely an individual endeavor but is deeply intertwined with one's relationship with God and community.

Community and Relationship in Well-being

While the inner struggle against logismoi and passions is intensely personal, the Orthodox tradition understands that healing and transformation do not occur in isolation. The Church community, with its liturgical life, sacraments, and network of relationships, provides the essential context for the spiritual journey. Within this community, relationships—particularly the relationship with a spiritual guide (Geronda or Starets) and with fellow believers—play a crucial role in supporting the individual's effort towards health and wholeness. This emphasis on community and relationship resonates strongly with psychological insights regarding the importance of social support, attachment, and the therapeutic alliance in healing processes.

Seeking guidance and support from an experienced elder (geronda) on the path to healing and transformation.

Seeking guidance and support from an experienced elder (geronda) on the path to healing and transformation.The Church liturgy itself is seen as a therapeutic environment, where individuals encounter divine grace, are reminded of their true identity in Christ, and participate in a corporate act of worship and healing. The sacraments, such as Baptism, Chrismation, Eucharist, Confession, and Anointing of the Sick, are understood as tangible means through which God's healing energy is communicated to the believer, addressing the spiritual, psychological, and physical dimensions of their being. The communal singing, prayer, and physical postures of worship (e.g., prostrations) also contribute to a sense of embodied participation and connection.

The Role of the Spiritual Guide

The relationship between a spiritual guide (Geronda or Starets) and their spiritual child is a cornerstone of Orthodox spiritual practice, particularly in the monastic tradition but also for lay people seeking serious spiritual growth. A spiritual guide is an experienced elder, often a monastic, who has traversed the path of inner struggle and gained discernment through prayer, asceticism, and God's grace. They offer guidance, correction, encouragement, and prayerful support